The Essential Worker

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, every day we heard the government and the media using the term “essential workers.” But who exactly are these essential workers?

You might say that they’re the doctors and nurses in hospitals, first responders like firefighters and police officers, and those who work on farms and in grocery stores to ensure we have food on the table. They’re people that keep planes, trains, buses, shipping, and utilities (water, electricity, natural gas, sewage, trash, cable TV, internet) running. Essential workers keep services functioning.

But is “essential” describing the workers themselves? Or only the work they do?

Do cleaning professionals meet the definition? Is it just some of us, or all of us? The cleaning industry worldwide focuses on cleaning as an investment in human, animal, and environmental health by making the scientific connection between cleaning and health.

My opinion is that workers in the cleaning industry have not been recognized as being essential during the COVID-19 pandemic. I see a disconnect between how the roles of cleaning professionals were described and what they experienced on the front lines. I see a disconnect between bathroom cleaning, shared space cleaning, high touch points, floor mopping, hard surface dusting, carpet vacuuming, and their value in decreasing the risk of transmission of germs and being infected.

Evolving guidance

On March 30, 2020, the mayor of Washington, D.C. announced a stay-at-home order that would go into effect on April 1, 2020. The order stated that residents may only leave their residencies to engage in essential activities, including to work at essential businesses that the order defined. Anyone found to be violating the order would be charged with a misdemeanor and subject to a US$5,000 fine and/or 90 days in prison. On the same day, the governors of Maryland and Virginia issued similar stay-at-home orders, but the penalties for violating those orders were different from those in Washington, D.C.

I have a hospital ID card that states: “The bearer of this identification card is an essential employee, and this identification card serves as an emergency pass through police, fire, and armed services checkpoints.” For COVID-19, I used it for the first time that first week of April 2020. It was 8:15 p.m., and I was two blocks from the hospital where I had been all day, training doctors, nurses, and other staff in the emergency department, on how to don and doff PPE. As I crossed the street, I was stopped by a police officer.

I flashed my hospital ID card, and he “thanked me for my service.” I looked over my shoulder, and 15 hospital workers, included cleaning staff who had attended my training, were crossing the street, and the officer stopped them. They were contractors and did not have the same hospital ID card that I carried. I intervened, explaining that they worked with me in the hospital. The police officer asked a few additional questions, and then we were on our way home.

I then realized that this was a problem. They had no ID to show they were essential workers. Maybe the situation would have been different if I had not been there, I don’t know, but it did worry me.

On March 19, 2020, the United States Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) issued a document entitled Essential Critical Infrastructure Workforce Guidance. This guide was primarily intended to help officials and organizations identify essential work functions, allowing them access to their workplace during times of community restrictions, such as stay-at-home orders.

As circumstances changed over the course of the pandemic, CISA published four additional updates to reflect the changing landscape of the nation’s COVID-19 response. The current Version 4.1, published August 5, 2021, provides guidance on how jurisdictions and critical infrastructure owners can use the list to assist in prioritizing the ability of essential workers to work safely, while supporting critical infrastructure operations. It provides guidance to reduce risk in several ways, including encouraging essential workers to be vaccinated, providing the appropriate protective gear, and creating and promoting policies and procedures that prevent the spread of illness among the essential workforces. This document illustrates that critical infrastructure is a large umbrella term encompassing sectors from energy, to health, to agriculture.

What does “essential” mean?

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “essential” as “extremely important and necessary.” Almost everyone would say their work is essential for some reason. But in a disaster, emergency, or pandemic, where there is an immediate threat to human life or injury, “essential work” is work that is necessary to meet the basic needs of human survival and well-being. An “essential worker” would be someone who does this work, but their job cannot be done remotely. “Essential work” includes the industries responsible for food, health, safety, security, energy, but cleaning and disinfection are often omitted.

Also, when I review the lists of essential workers from federal and state governments, the one group that appears never to make the list is cleaning professionals. They work on the front lines in many essential facilities every day, completing essential work (cleaning and disinfection).

Still, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, cleaning professionals have experienced a lack of adequate safety measures, supplies such as gloves and face masks, risk compensation, and training and education. We don’t know how many have contracted COVID-19, but the risks have been high among front-line cleaning professionals who came from diverse backgrounds and were required to leave their homes every day. It makes me wonder why they weren’t considered essential.

But they continued to clean and do the jobs that sustained many other industries while many of us were able to work from the safety of our homes. It is important to note that all essential workers should be guaranteed the right to a workplace free from health and safety hazards. When hazards are present, such as infectious germs, they should be provided training and resources to mitigate the risks of being infected.

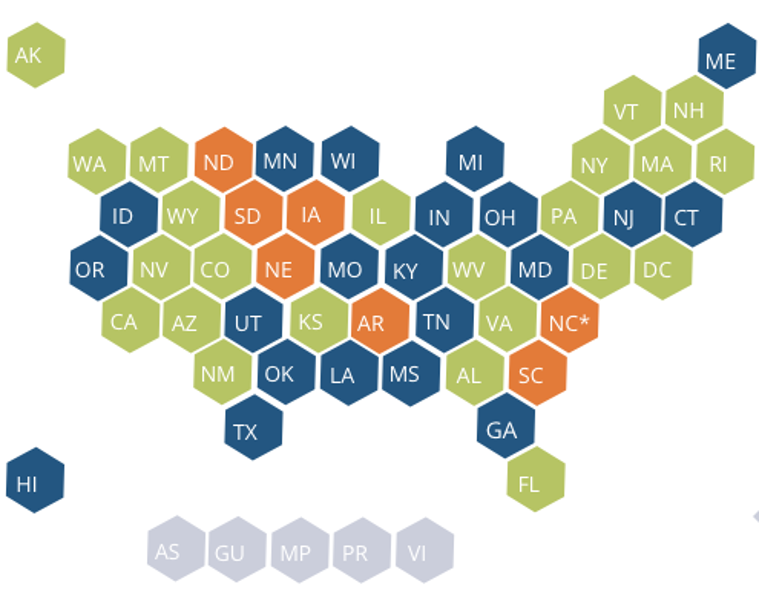

COVID-19: Essential workers by states

Twenty-two states and Washington, D.C. (green on the diagram below) have developed their own lists of who needs to continue to work under stay-at-home orders. States have added and subtracted essential worker categories and sectors based on what makes the most sense for them. Between the federal guidelines and state essential worker orders, several major sectors overlap, including:

- Energy

- Childcare

- Water and wastewater

- Agriculture and food production

- Critical retail (grocery stores, hardware stores, mechanics, etc.)

- Critical trades (construction workers, electricians, plumbers, etc.)

- Transportation

- Nonprofits and social service organizations.

Critical trades—Where cleaning professionals belong

In my opinion, I would like to see the federal government and every state list cleaning professional as a “critical trade.”

The critical trades sector is composed of professionals trained in any number of key services that are critical to keeping homes, offices, and other buildings operating. Some of the professions currently considered a part of this sector include electricians, plumbers, HVAC technicians, wastewater treatment plant operators, and exterminators.

CISA’s guidelines, as well as many of the states who have adopted their own, consider workers in these trades “critical infrastructure workers” and recognize the work they perform as “necessary to sustain and protect life.” While many workers have been teleworking from home, critical tradespeople, just like cleaning professionals, have been working to keep office buildings and other facilities operating. And while folks during the COVID-19 pandemic have transitioned to spending most of their time at home, tradespeople have continued to uphold safety and quality of life standards for residences, offices, hospitals, nursing homes, and commercial buildings.

For the 21 states deferring to the federal government’s CISA guidelines, a wide range of trades are considered essential, including those supporting the construction, maintenance, or rehabilitation of several sectors, from energy to public works and infrastructure to communications.

The 22 states and Washington, D.C. that have developed their own guidelines use similarly broad language to encompass as many of these professionals as possible.

Colorado, for example, refers to the construction and skilled trades broadly, but only gives a few examples, relying heavily on “including, but not limited to” language.

Similarly, Alabama simply refers to any workers in “construction or construction-related services” as essential.

Illinois has taken a slightly different approach in that the state specifically lists some examples of what it considers critical trades in its essential worker order. These include, but are not necessarily limited to, plumbers, electricians, exterminators, cleaning and janitorial staff, and security workers.

Massachusetts guidance gets even more specific, with the state listing which “construction-related” activities it considers necessary to maintain the safety, sanitation, and essential operation of residences, businesses, and buildings, such as hospitals. The state’s list goes on to include specific types of worksites and projects considered essential too.

Federal guidelines

Seven states have no guidance. Of the 43 states with essential worker orders or directives, 21 (blue on the previous page) now defer to the federal definitions developed by CISA. On August 10, 2021, CISA published a 23-page Advisory Memorandum on Ensuring Essential Critical Infrastructure Workers’ Ability to Work During the COVID-19 Response. On page 23, under the section heading Hygiene Products and Services, it states that essential workers include “workers providing disinfection services for all essential facilities and modes of transportation and who support the sanitation of all food manufacturing processes and operations from wholesale to retail.”

The graphic that accompanied the CISA Advisory Memorandum included 16 sectors listing Essential Critical Infrastructure Workers. Unfortunately, cleaning professionals did not make the graphic, but they did make the document.

COVID-19 vaccine prioritization for essential workers

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) provides recommendations for who will receive the COVID-19 vaccine while there are limited doses, taking into consideration the vaccine’s physical effect on different age groups, ethnicities, and people with underlying medical conditions.

CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Shots guidance, published on October 27, 2021, stated that “people ages 18-64 years at increased risk for COVID-19 exposure and transmission because of occupational or institutional setting may get a booster shot based on their individual risks and benefits.” CDC also provided an example list of workers who may get COVID-19 booster shots, and cleaning professionals were not on the list:

- First responders (e.g., health care workers, firefighters, police, congregate care staff)

- Education staff (e.g., teachers, support staff, daycare workers)

- Food and agriculture workers

- Manufacturing workers

- Corrections workers

- U.S. Postal Service workers

- Public transit workers

- Grocery store workers.

I can’t stress enough how important it is to consider the words we use when emphasizing perspectives and priorities during a situation like the COVID-19 pandemic or any emergency. When we review how the government and the media used the phrases “essential workers” and “essential work,” I think this helps explain why so many people in the cleaning industry feel left out and not appreciated. We know that some of our essential workers, the ones that continued to report to duty and risk their lives and the lives of their families, experience greater rates of housing instability, food insecurity, and financial hardship. And then, many of them were infected and had COVID-19 disease.

A study published November 9, 2020, by Thomas Selden and Terceira Berdahl from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in the Journal of American Medical Association’s Internal Medicine, estimated that up to 74 million Americans nationwide were at heightened risk of becoming infected, either because they were essential workers themselves, or shared households with someone who was. This study also stated that up to 61% of these essential workers had underlying health issues that put them at increased risk of severe COVID-19 should they become infected.

The risks to essential workers in all disciplines who could not work from home were clear from the beginning of the pandemic. But the risk of transmission to household members living with essential workers was also equally important when considering the potential for disease transmission. It is time to recognize the increasing risks that cleaning professionals take to do essential work to keep cities and towns functioning throughout the pandemic. I know the cleaning professionals in our industry are “essential,” and they are definitely not “expendable.”

References

National Conference of State Legislatures COVID-19: Essential Workers in the States. Accessed Nov 2, 2021. https://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/covid-19-essential-workers-in-the-states.aspx

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency, Advisory Memorandum on ensuring Essential Critical Infrastructure Workers’ ability to work during the COVID-19 Response. Accessed Nov 2, 2021. https://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/covid-19-essential-workers-in-the-states.aspx

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Shots updated Oct 27, 2021. Accessed Nov 2, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/booster-shot.html

Selden TM, Berdahl TA. Risk of Severe COVID-19 Among Workers and Their Household Members. JAMA Internal Medicine 2021;181(1):120–122. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6249

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2772328?resultClick=1 rk