The Sustainable Sweep: EPR, Circularity, and the Future of the Cleaning Industry

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) regulations are no longer a theoretical conversation in the cleaning industry. They are here, expanding state by state, and reshaping how products are designed, packaged, and brought to market.

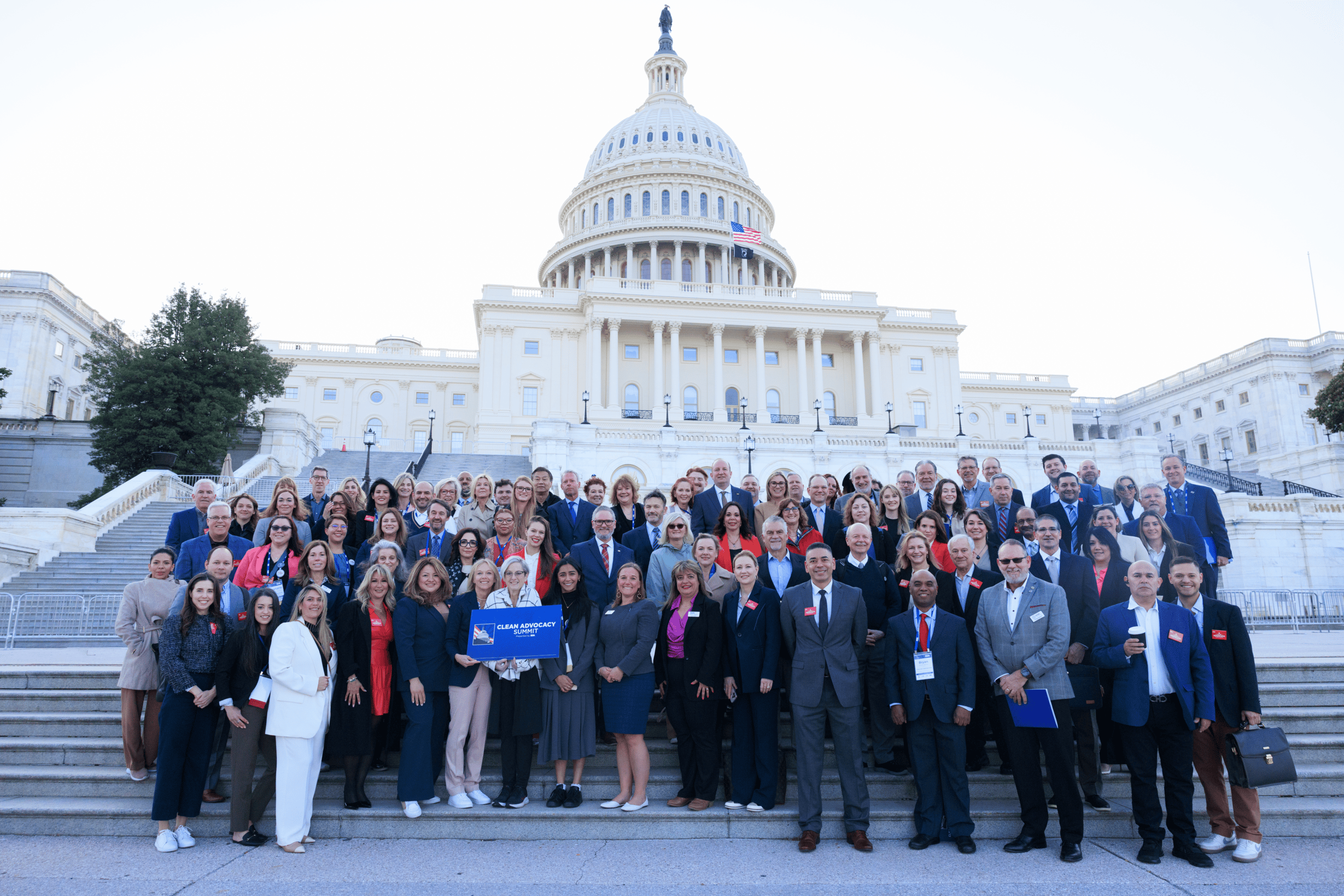

In a recent webinar hosted by ISSA, Rebecca Schwartz Altholz, EPR data manager at Reverse Logistics Group (RLG), and John Nothdurft, the ISSA director of government affairs, unpacked the growing wave of packaging legislation, what it means for manufacturers and distributors, and how businesses can prepare for the shift toward a circular economy.

What EPR means in practice

Governments across the United States are grappling with ballooning waste management costs, mounting landfill pressure, and increased consumer demand for accountability. EPR laws shift responsibility away from taxpayers and municipalities and place it squarely on the companies that make and sell products.

“EPR law creates a system where government sets the rules, producers fund the solution, and producer responsibility organizations make it all happen,” Altholz explained. These organizations, known as PROs, collect fees from producers and use them to support recycling infrastructure, public education, and reporting obligations. Crucially, the fees are not flat: they vary depending on the amount of packaging used and how recyclable or reusable it is. That fee modulation creates a powerful incentive for companies to cut down on waste and innovate with sustainable packaging.

Where U.S. laws stand today

At present, seven states–Oregon, Colorado, California, Maine, and Minnesota, and most recently Maryland and Washington–have active EPR laws for packaging, with reporting deadlines already underway or quickly approaching. Of the seven, four have reports due this year. Meanwhile, at least a half-dozen other states, including New York, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Hawaii, are considering legislation.

One estimate predicts that 19 states will have packaging EPR laws by 2030. For businesses selling into multiple markets, that means navigating a patchwork of requirements.

“Every state is writing its own playbook,” Altholz said. “We haven’t seen harmonization yet. And frankly, I don’t expect it anytime soon.”

Nothdurft agreed, pointing out that even electronics, which have been under EPR mandates in 26 states since the early 2000s, still lack federal standardization. “Congress usually doesn’t act until its hand is forced,” he said. “But for now, producers have to deal with complexity and keep up with each state’s rules.”

The cost of non-compliance

Flying under the radar isn’t an option. Penalties for non-compliance are steep. California’s SB 54, for instance, allows for fines of up to $50,000 per day. States may also publish lists of non-compliant producers, a reputational blow that can quickly erode consumer and investor trust.

According to Altholz, enforcement is already ramping up. “What we have heard is that if a company had made good-faith efforts, then the states and [PROs] would be more understanding. They haven’t followed through on enforcement yet, so we aren’t exactly sure how this is going to play out.”

Five steps to EPR compliance

Altholz outlined a straightforward roadmap for companies:

- Understand the landscape: Know which states you operate in, their rules, and whether your products qualify as obligated.

- Check your data: Audit your packaging data for gaps or inconsistencies.

- Fill in the blanks: Collect missing information from suppliers and ensure accuracy.

- Forecast costs: Estimate EPR fees so finance teams can prepare.

- Submit and pay: File reports properly formatted for each jurisdiction and pay fees on time.

Following these steps early can save businesses from costly mistakes later.

Special challenges for the cleaning industry

The cleaning industry faces unique hurdles in adapting to EPR. Many products are sold as concentrates, environmentally efficient but chemically complex. Some state regulations don’t clearly differentiate between retail and commercial use, leading to confusion over whether certain products are covered.

“This is probably the number one question we get,” Nothdurft said. “Even if the law mentions household products, cleaning products can fall under the definition depending on how statutes are written. It’s not always obvious.”

The tension is especially sharp with concentrated formulations. On one hand, concentrates reduce packaging waste and transportation emissions. On the other, they may raise concerns about safety and environmental hazards if not handled properly. “It creates competing issues,” Nothdurft noted, citing overlap with EPA pesticide regulations, PFAS restrictions, and state-level chemical bans.

Looking ahead

Despite the complexities, both speakers stressed that EPR isn’t going away. Instead, it represents an opportunity for forward-thinking companies to innovate, streamline packaging, and position themselves as leaders in sustainability.

“The worst thing you can do is assume you’re exempt and sit back,” Altholz cautioned. “Don’t fly under the radar. Find out for sure if you have obligations, and if you do, take steps now to get your data ready.”

Nothdurft echoed the point: “This is expanding, not shrinking. The companies that engage early and build compliance into their operations will be the ones best positioned to compete in the circular economy.”

For more information, check out ISSA’s recently updated EPR Guidance.